Can You Cure a Domestic Abuser?

A class developed in Duluth, Minnesota, has heavily influenced how domestic abusers are rehabilitated across the U.S. But critics question whether it works.

The photograph above shows Andrew Lisdahl and his fiancée, Theresa, at their home, along with Andrew's daughter with his ex-wife (left) and one of Theresa's daughters (right).

Andrew Lisdahl was mad. His wife, Gretchen, had smoked a cigarette, a habit he detested. They fought, and Gretchen spent the night at a friend’s house. The next day, Andrew drank a bottle of tequila and hitched a ride to the stained-glass studio where Gretchen, an artist, gave lessons. When Andrew found her, he grabbed her left hand and tried to remove her wedding ring, but Gretchen fought him off. As Andrew stumbled away, he took Gretchen’s car keys and phone.

After work, Gretchen’s father drove her back home to retrieve her things. Inside, Andrew had been passed out on the couch, but he woke up and yelled at Gretchen, “Get the fuck out!” When she didn’t, he grabbed her by the hair, dragged her into the living room, threw her on the carpet, kicked her in the chest, and pinned her to the ground. As Gretchen’s father approached the house, Andrew let her go and she was able to escape.

Gretchen went to a police station near their home in Superior, Wisconsin, and showed an officer on duty the red marks coloring her sternum. When police arrived at the house and knocked, Andrew announced from inside that he was aiming a shotgun at the officers’ faces. A SWAT team was summoned. Soon after, Andrew emerged, hands in the air, wearing only a pair of pajama bottoms, and surrendered. Police said they recovered a loaded shotgun next to the door. (Andrew denies that it was loaded.) He was arrested and charged with misdemeanor domestic battery, to which he pleaded guilty. (Many details of the encounter are contained in a police report. This abuse incident, and others described in this article, have been corroborated with both Andrew and Gretchen.)

After two years of court proceedings, Andrew found himself sitting in an austere conference room in Duluth, Minnesota, with a dozen other men, most convicted of similar crimes. In the United States, domestic abusers are rarely sent to prison. More often, as in Andrew’s case, they are sent to a special class designed to teach them to refrain from physical violence. The methods employed by these groups, known formally as “batterer intervention programs,” or BIPs, vary—there are 2,500 in the United States alone, according to one study—but most base their instruction on ideas from second-wave feminism, striving to educate men about the ways in which the harm they visit on their romantic partners mimics the larger, repressive structure of patriarchy.

For Andrew, then 34 years old, being court-ordered to attend a class for wife-beaters was a shameful low point. It signaled to everyone that he had violated an immutable taboo, impressed upon him since childhood: Men do not hit women. He had been arrested for battering Gretchen five years before, in 2010, but she had requested that he be let off, and the charges had been reduced to disorderly conduct. Since his latest arrest, Andrew hadn’t wanted to speak to anyone about the classes, afraid of where the conversation might go. As he waited for class to start, he stared at the dusty umber carpeting, inwardly vowing to avoid speech or eye contact.

Andrew was horrified when, a few minutes in, the facilitator leading the group asked him to introduce himself to his classmates. Explain, the man said, smiling, why you’re here.

Andrew stood up. “I’m Andrew,” he said, eyes still fixed on the floor. “I’m here because I hit my wife, Gretchen.”

Sinking back into his seat, Andrew was suddenly overcome by an unexpected sense of relief. He still didn’t want to be in the room, at all, but speaking his stigma aloud—admitting, in semipublic, the hideous thing he’d done—felt, to his surprise, kind of good. Over the next six months, he continued to unburden himself to the men, and they to him. Soon, Andrew would come to believe—as would Gretchen—that the class was the only thing capable of exorcising the evil pieces of his spirit and making him a decent man.

Considered in aggregate, physically abusive men constitute a catastrophic public-health hazard. While research suggests that men and women employ violence in relationships at roughly equal rates, the damage inflicted on women is far more severe. Nearly half of all homicides of women in the U.S. are committed by a victim’s romantic partner. Globally, the leading cause of nonfatal injuries to women—ahead of car crashes, falls, and accidental poisonings—is domestic violence.

For most of American history, authorities treated domestic violence with benign neglect. Legally, the act of assaulting one’s spouse was only widely criminalized within the last century or so. Even then, cops saw fisticuffs between lovers as a private sport they had no business refereeing. (A 1975 training bulletin issued by the police department in Oakland, California, advised that, instead of making an arrest, officers should “encourage the parties to reason with each other.”) District attorneys, meanwhile, resisted prosecuting abusers, often because victims—many in danger of further attacks—were reluctant to pursue charges. In general, all but the most egregious cases went unpunished.

An organized effort to take such violence seriously began in the early 1970s, when activists set about publicizing the social problem then known as “wife battering.” A flurry of research—epitomized by Erin Pizzey’s collection of case studies, Scream Quietly or the Neighbors Will Hear—gave rise to a network of support groups and women’s shelters. In 1980, a small band of activists gathered in Duluth with the goal of addressing the justice system’s failings. The creators of the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (DAIP), as it became known, devised a revolutionary plan to help communities respond aggressively to the phenomenon. To prevent cases from being ignored, relevant municipal agencies, including police, courts, and social workers, would carefully coordinate their actions. Women would be assigned advocates to help them understand their legal options and seek orders of protection from their partners. To make sure cops did their jobs, arrests for certain offenses would become mandatory, and prosecutors would try cases even without cooperation from victims. After a pilot run of the program in Duluth appeared to reduce assaults, the “Duluth model” of responding to domestic violence was adopted by cities across the country.

But there was one aspect of domestic violence for which the Duluth model didn’t have a solution: what to do with the abusers. While activists agreed that the threat of arrest and incarceration was an important deterrent to domestic violence, it wasn’t a cure. Batterers couldn’t be locked up forever, and the prison environment was hardly conducive to reducing aggression. Ellen Pence, a cofounder of a Minneapolis women’s shelter, was one of DAIP’s organizers. In her experience working with victims, Pence had observed that many men who hit their partners did so repeatedly, over many years. Such habitual batterers, in her opinion, required not just punishment, but some form of reeducation.

At the time, little was known about the causes of domestic violence. Many psychologists viewed abuse as the side effect of some other difficulty—alcoholism, an inability to handle stress or anger, poor communication skills. Not infrequently, blame was placed on a woman’s failure as a wife or girlfriend. One study, published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 1964, asserted that spouses of abusive men tended to be “aggressive, efficient, masculine and sexually frigid.”

Like many contemporary feminists, Pence saw the phenomenon differently. Abuse, in her view, wasn’t an individual problem, but a social one. For millennia, men had been taught that it was their right to control women, by force if necessary. Domestic violence was the means by which a man exercised this power on an interpersonal level. Far from a dysfunction, it was a rational tactic—a tool for patriarchy. Yet men had grown so used to this system, into which they’d been socialized since birth, that they never thought to question its correctness.

If men were conditioned to become oppressors, the only way to change them, Pence reasoned, was to denaturalize this arrangement. Inspired by the work of the Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire—who, in his classic Pedagogy of the Oppressed, described educating peasants by posing questions that foster dialogue—Pence wondered whether she might be able to challenge, through conversation, the ideas motivating domestic violence. Along with a Duluth City Council member named Michael Paymar, she drew up a curriculum for a series of support groups meant to help men come to terms with their destructive behavior, take ownership of their actions, and, with luck, stop injuring women.

Launched in the mid-1980s, Pence and Paymar’s program was not the first men’s group for batterers—several other programs, using different techniques, had already sprung up in other cities—but it proved the most influential. The Duluth curriculum’s innovation, of attacking the societal roots of abuse, met with approval from activists and victims’ advocates. Lawmakers found in the groups a convenient means of dealing with the new wave of domestic-violence arrests. Over the next three decades, the curriculum spread rapidly, until programs advancing the theory that domestic violence was underpinned by sexism had been established in every state in the country. Over time, the “Duluth model” would come to refer to those specific gatherings, and their pedagogical focus on dismantling patriarchal norms, rather than to its original plan for coordinated community action.

But as their popularity grew, Duluth’s men’s groups faced a backlash. As researchers began conducting more studies, they found that the early psychologists who had ascribed domestic violence to individuals’ underlying problems, such as addiction and trauma, were, to an extent, correct. Studies showed that the Duluth approach, with its broad social message, had little effect on whether men actually re-offended. It was also criticized as ill-suited for addressing assaults committed by women and within same-sex partnerships. Yet today, Duluth’s backers continue to argue that its gender-based approach is the only one capable of getting at the roots of male battering. Men's groups remain the most common method of attempting to reform the domestically violent, and in these groups, the Duluth curriculum is the most frequently used approach.

The offices of DAIP occupy the third floor of an inconspicuous brick building, distinguished, mainly, by a faded white sign above the front door reading Home of the Duluth Model. The organization hosts men’s groups in a room fronted by a big picture window overlooking Lake Superior, which, when I visited in mid-March, was still frozen over and skinned with snow.

On a Thursday morning, I watched twelve men in heavy winter coats shuffle inside and take seats in a semicircle of office chairs. In exchange for receiving probation instead of incarceration, men agree to attend 27 classes at DAIP, each lasting 90 minutes. The group seemed, by all appearances, a thoroughly average sampling of midwestern manhood. Most of the men were deep into middle age, but a few were younger, and they sat hunched over, hiding in their phones. (DAIP allowed me to sit in on its groups with the condition that I not include the participants’ real names or any identifying details. The names of the participants’ victims have also been changed.)

At the front of the room stood the class’s facilitators, Jen Rouse, one of DAIP’s newest staffers, and Scott Miller, one of its codirectors. According to DAIP’s lengthy instructor manual—the core of the Duluth curriculum—the goal of a facilitator is threefold: to challenge men’s patriarchal views, to help them take responsibility for their past violence, and to inculcate a new, more egalitarian set of beliefs. Each class has two facilitators, one man and one woman, to habituate abusers to seeing men and women on an even footing. Many of the men, Rouse told me, publicize their disdain for the female facilitators with theatrical displays of anger, silence, or hostile body language. “Some of the men, when they first come in, they can’t even look at me,” said Rouse, a small, cheerful woman in her 30s. “But over time they engage.”

Critics have caricatured the Duluth approach as one in which men are shamed and bullied into taking on feminist-approved ideas. In truth, the meetings are free of jargon such as “patriarchy” and “misogyny,” and DAIP’s facilitators seldom lecture or admonish. Rather, they try, in the words of the facilitation manual, to “create a process of change.” This usually takes the form of peppering the men with questions. The goal is to encourage the men to confront their assumptions about power, gender, and privilege. The best situation a facilitator can find himself in, Miller told me, is to ask a man a question for which he has no answer. That’s when the growth happens.

The class began with a short video illustrating the week’s topic: emotional abuse. It depicted “Steve,” a jittery man with a chinstrap beard, accosting his estranged wife, “Cherie,” outside her home, as she’s taking out the trash. By visiting the house, Steve, we learn, is violating an order of protection, but he pleads with Cherie to let him move back in. “I just feel like I’m starting to change, okay?” he huffs. Unmoved, Cherie threatens to call the police.

“You’re not going to know what to do without me!” yells Steve.

Cherie starts marching inside. “You’ve got 10 seconds and I’m calling the cops.”

“10-9-8-7-fuck you!” Steve screams, kicking the trash can.

The class hooted with laughter.

Afterward, Miller—tall and lanky, with a salt-and-pepper goatee and a springy energy that is echt Minnesota—asked the class to describe how, exactly, Steve had been emotionally abusive. Rouse, armed with a dry-erase marker, compiled their responses.

“He started being nice at first,” offered a flannel-shirted man—one of many—whom I’ll call Liam. “But he was just trying to manipulate her.”

The men, Miller explained to me later, arrive in the class with different levels of resistance to its teachings. At first, many deny having done anything wrong, claiming that it was self-defense, or that it was an accident, or—the most common justification of all—that their partner drove them to do what they did. The first step in helping the men, therefore, is to make them fully aware of their abusive behaviors, of which physical violence is only one component. In the 1980s, DAIP developed a now-famous diagram, the “Power and Control Wheel,” to illustrate the variety of tactics abusers use to dominate their partners. These include more subtle forms of tyranny, including emotional abuse (“putting her down”; “making her feel bad about herself”) and exercising male privilege (“making all the big decisions”; “acting like ‘the master of the castle’ ”). One-third of the Duluth classes were allotted to educating the men about this spectrum of abuse, the rest to teaching them different, more equitable forms of conduct.

An important step in creating change was to help the men become aware of the misogynist judgments that served as justification for their violence. Once their unconscious thoughts about gender relations (“She needs to listen”; “I’m right”) were exposed, they could be amended.

Some men, however, required special encouragement to reflect on their actions. Miller pointed to one of the class’s youngest attendees, Jimmy, who had been to three classes but had yet to speak.

“Jimmy,” Miller said, “what’s something that you’ve done that’s emotionally abusive to your partner?”

“I can’t think of anything,” Jimmy mumbled, arms folded, chin to his chest. “That video? … I’m in the woman’s spot.”

Miller paused. It was a common strategy for abusive men to identify as victims. Whenever an offender sought to minimize or deny his behavior in this way, it was the facilitators’ job to challenge him. When facilitators failed to hold a man accountable for patriarchal behavior in class—self-pity, chauvinist jokes, disparaging their partners, and so on—they were, in Ellen Pence's phrase, said to be “colluding” with the abuser and giving him license to be violent.

“But what’s the thing that you’ve done that’s emotionally abusive?” Miller countered.

Jimmy shrugged.

Wayne raised his hand. “The world I was living in was narcotics and partying,” he said. “I cared about my kids. I loved Diane”—in class, men are required to use their partner’s given names instead of saying “my wife” or “my girlfriend,” as a means of reminding them that women are human beings, with individual identities—“but I loved my party life better.”

Most of the men in the room, it became clear, had issues with substances, generally alcohol or opioids. Facilitators generally like to give the men free rein on what topics they explore—Miller told me exit interviews showed that participants learn most from hearing each other’s experiences—but are quick to question men who cite addiction as a reason for their violence. For a facilitator, allowing the men to avoid accountability by placing the blame on substances would be a form of collusion.

Trying to shift topics, Rouse asked the class to consider how their abuse had affected their families. A critical means of compelling change is to get men to see the negative ramifications of their violence on themselves and others. In truth, Miller told me later, patriarchy is not pleasant for men either. In class, abusers are constantly telling him that, given the chance, they’d prefer to be in loving, equitable relationships with women—they just don’t know how. But convincing the class to focus on their physical abuse instead of their substance abuse, the facilitators agreed, remained a challenge.

“If they have PTSD or an anxiety disorder and that’s getting in the way of their becoming someone new, yeah, fix that,” Miller said. “But if you think someone is going to sober up and stop being abusive, they’re not. They’ll just be sober batterers.”

In March 2003, during the earliest days of the Iraq War, the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, received orders to capture and hold a pair of bridges in the city of Nasiriyah. Andrew, a 20-year-old mortarman on his first deployment, found himself trapped at the center of a hellish, week-long urban firefight, lobbing explosives at dangerously close targets in every direction. Several years later, after his third tour in Iraq, Andrew returned home to Superior. The VA diagnosed him with PTSD and prescribed him medication. A few years later, he married Gretchen and they had their daughter.

Gretchen told me that, during their marriage, she could almost set her watch by when her husband would start hurting her. After a blowup, there’d be a honeymoon period lasting a week or two, during which Andrew would be the nicest man she’d ever met. But then tension would rise, and another version of the man—she called him “Bad Andy”—would return. Finally some small frustration—a late meal, a dirty shirt on the floor—would set him off, and he’d explode. (Andrew denied that he regularly hurt Gretchen beyond the two occasions, in 2010 and 2015, when he was arrested for domestic abuse. He said, however, that there were instances in which Gretchen attacked him, as well as fights that led to violence on both sides. Gretchen said she used violence only defensively.)

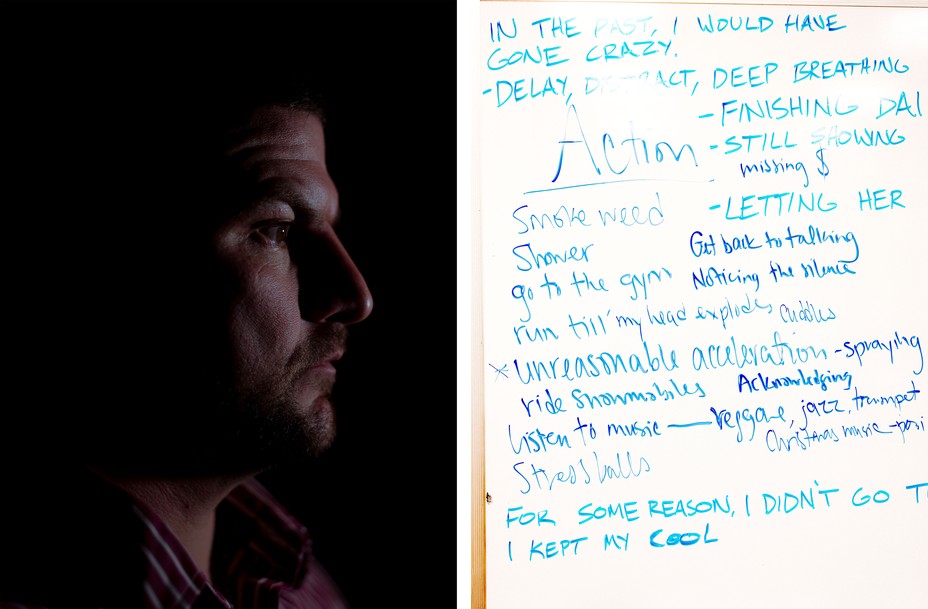

By the time Andrew was sent to Duluth—a short drive across the Wisconsin-Minnesota border from his home in Superior—he was frightened by his own capacity for violence. He wasn’t aggressive just with Gretchen; he was aggressive with everyone. He’d lost count of the number of bar fights he’d started. He didn’t have much confidence, though, in the men’s group’s ability to help him change. His experience with the VA, which had once assigned him to what he described as a “cookie-cutter” anger-management class, had soured him on the efficacy of “programs.” Yet, DAIP felt like his last chance. After his second arrest, Gretchen had finally left him. He loved, more than anything, being a father to his 9-year-old daughter, and, while he and Gretchen were sharing custody, he worried that he would lose her.

For the first month of class, Andrew slumped in his seat, arms crossed, glaring at the whiteboard. He deeply resented having to be there, and he instinctively hated every other man in the class because they’d done what he’d done. While Andrew understood, in theory, that he was responsible for his actions, some small, pernicious inner voice kept telling him that he’d had no choice—that it really wasn’t his fault, and he didn’t deserve to be there. In an odd coincidence, Gretchen had started working part-time in a blown-glass gallery that shared a building with DAIP. She would see Andrew stomp downstairs after class, looking pissed off. She worried that he was getting worse.

Soon, however, Andrew began recognizing himself in some of his classmates. When one guy told a story about demolishing his girlfriend’s modem with a shotgun, Andrew found himself nodding along. He had punched out a girlfriend’s TV once. When he saw the Power and Control Wheel, he recognized, with a lurch in his stomach, most of the behaviors as stuff he’d done. After a few weeks, Andrew worked up the courage to talk. He shared an anecdote about his day, then glanced up and caught a few guys making eye contact with him. That was the biggest reassurance: someone being willing to look at you.

Gradually, Andrew felt the stirrings of camaraderie. Some of his classmates clearly weren’t ever going to change—an old guy who wouldn’t shut up about his wife’s spending habits, a young guy who was just biding his time until the final class—but a lot of the men seemed okay. He’d always been most comfortable in all-male environments, where he felt like he could be himself. The relationships with coworkers and his buddies in the Marines had each created a particular type of intimacy, but a limited one—nothing too personal. In the men’s group, though, you could say almost anything and know no one would judge you for it.

After a couple months of classes, Gretchen noticed that Andrew was acting different. The two of them would meet up every few days to hand off their daughter. The encounters had been tense at first, but Andrew had begun to soften. He stopped making backhanded compliments and showed an unprecedented willingness to compromise, offering to cover for her when she needed a babysitter. She didn’t know quite where the shift had come from, but she hoped it would last.

In her writings, Ellen Pence, who died in 2012, was insistent about seeing domestic violence within its proper context. “When a man slaps a woman,” she would often tell staffers, “it doesn’t happen in a vacuum: It’s a historical act.” With regards to Duluth, Pence would also often acknowledge that the city’s men, many of them working class, were uncommonly burdened by personal problems—poverty, stress, addiction, trauma—some stemming from childhood, others from the collapse of the region’s ore-mining industry. But, while Pence allowed that these factors might exacerbate abusive behavior, she denied that anything other than male entitlement, born of patriarchy, could cause a man to hit his partner. Though the facilitator’s manual, which Pence coauthored, counsels sympathy for troubled men—“We can’t discount their pain and scars”—it warns against allowing “individual experiences” to serve as “an explanation” and “an excuse” for them to continue their oppression. Letting the men think of themselves as victims ran the risk of letting them escape blame for their actions.

“A lot of times, the men are victims,” one facilitator told me. “Just not in that room.”

Pence also dismissed the idea that eons of male domination could be solved with psychotherapy. While counseling might help an abuser work through certain individual issues, it did nothing, in Pence’s opinion, to address the larger social and political realities inspiring his violence. Moreover, she felt that by “psychologizing” the problem of domestic violence, therapists were vulnerable to collusion. They might allow their clients to see their abuse simply as a by-product of their past trauma or other difficulties. But as she saw it, each abuser, regardless of background, was motivated by a common sense of male entitlement.

“It really comes down to a very simple thing,” Michael Paymar, Pence’s colleague, said. “Men who batter want what they want when they want it.”

Duluth’s renunciation of individual psychology in favor of what critics have called a “gender political model” of abuse has drawn scorn from mental-health professionals. In the view of most psychologists, domestic violence can be caused by many things. While culture—particularly the degree to which domestic violence is tolerated or encouraged by a society—plays a role in producing batterers, scholars argue that it is impossible to isolate a single element, like male entitlement, from what is often a grisly gnarl of psychological and biological influences.

Most studies, including two published by the federal National Institute of Justice (NIJ) in 2003, have shown that men’s groups modeled on Duluth’s have, at best, a minimal effect on whether participants continue to abuse their partners. At the same time, other types of group-based interventions, including various forms of cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT—an apolitical method of helping abusers change the thought patterns that lead to violence—have proven little more effective. Perhaps because better alternatives haven’t presented themselves, many state-mandated programs are required to adopt Duluth’s philosophical framework.

This has led some domestic-violence researchers to worry that Duluth’s dominance has made it difficult to try new approaches. Carla Stover, a professor at Yale University’s School of Medicine who studies domestic-violence interventions and, as a clinical psychologist, has counseled abusive men, told me that, while the Duluth curriculum might work for some offenders, many would likely find the lessons inappropriate to their situation.

“If your problem is, say, emotional dysregulation”—an inability to appropriately handle overwhelming feelings—“how is focusing on societal norms about gender roles going to help you?” Stover said.

In published rebuttals to its detractors, DAIP has claimed that its men’s groups work, but only if correctly implemented. Virtually all studies, including the NIJ one, were conducted on groups outside of the city of Duluth, many of which, Paymar contends, failed to follow the program’s guidelines. (Paymar and others have questioned the methodology of the NIJ research.) Though DAIP offers trainings, it has no system of licensing or accreditation, which means that a men’s group can claim to abide by its teachings but resemble it in name only. DAIP also emphasizes that the groups were never intended as a cure-all solution to domestic violence, but only one element of its original Duluth model, requiring a coordinated community response. Many cities, however, use just the groups.

“The Duluth curriculum was one of the early batterer-intervention programs that centralized victim safety, held offenders accountable, and offered men who batter concrete ways to change,” said Paymar. “Since BIPs emerged, programs are trying new techniques which are good.”

Perhaps one reason for DAIP’s limited effectiveness is that, by its own pessimistic assertion, many men are, unfortunately, unlikely to reform. While group facilitators, per the DAIP manual, “must have an unshakeable belief that within each of us is the capacity to change,” they should also “have no illusions that the majority of offenders will stop their use of violence.” Domestic violence, Miller told me, will likely stick around until society can figure out how to rid itself of male entitlement.

“We can have an impact, but it’s still a generational process,” he said. “This problem is so long-standing, so entrenched, so historical—to think one agency has the power to end that violence is ludicrous.”

Recently, frustration with Duluth, as well as CBT-based methods, has led some states to begin experimenting with alternative approaches to their men’s groups. Several years ago, after an internal review by the Iowa Department of Corrections found that its intervention program—a hybrid of Duluth and CBT—was so ineffective that it constituted “a waste of taxpayer dollars,” the agency adopted a new method, one that took a radically different view of abuse.

Developed by Amie Zarling, a professor and clinical psychologist at Iowa State University, “Achieving Change Through Values-Based Behavior,” or ACTV, rejects the idea that there is any single root cause of domestic violence. According to Zarling, sometimes violence is deployed to preserve male dominance, but often it’s simply a coping mechanism for extreme distress. For many men, Zarling said, being violent is a way of fending off unpleasant emotions, such as vulnerability, shame, jealousy, or anxiety.

“In the moment, violence can actually be extremely effective at helping someone avoid feeling bad,” Zarling told me. “Abusers learn that when they punch someone, they get some kind of relief from pain. And their brain remembers that. It’s a very under-the-skin, insidious process.”

One solution, Zarling posited, was to give abusers a way of making their distress manageable. Whereas Duluth is predicated on preventing violence by challenging men’s beliefs, and CBT by changing their thought processes, ACTV (pronounced “active”) takes a different approach. Instead of trying to alter what men believe or think—“It’s really, really hard to change someone’s thinking,” Zarling said—ACTV strives to help abusers accept their thoughts but respond differently to them. Ideally, an abuser will learn to become aware of unpleasant feelings but to not let them control him. In addition to teaching abusers about patriarchy, ACTV is also teaching them mindfulness.

Like Duluth, ACTV imparts its lesson in small seminars. When I visited one of its classes, in Des Moines, last July, I watched a program coordinator, Lucas Sampson, and the men discuss the difference between “away moves”—things people do to avoid uncomfortable feelings that take them away from their values—and “towards moves”—things people do to deal productively with those feelings and take themselves toward their values. The trick, Sampson explained, was for men to be able to notice and identify difficult emotions before they led them to act out in ways they would later regret.

“You know the ‘Check Engine’ light in your car?” Sampson asked. “When that comes on, what do we do?”

“Put a picture over it,” one man replied. Everyone laughed.

“Right,” Sampson said. “And that’s okay for a little bit. But if I ignore it, eventually … ?”

“Your engine gets fucked.”

“Exactly. Anxiety, stress, anger—those are your ‘Check Engine’ lights. If you don’t deal with them, bad things happen. You’re putting yourself and your family at risk.”

ACTV seemed less of a strain on the facilitators. Their primary task is to help the participants act in accordance with their own values and goals, which they are asked to define early in the program—“Stay out of jail”; “Raise my kids.”

At the same time, facilitators lacked the comfort of thinking that they were much different than the abusers. “We’re on the same level as the guys,” Sampson told me. “I use these mindfulness techniques—I think, ‘Is what I’m doing right now an away move or a towards move?’—in my own life, with my wife, my kids.”

Results for ACTV are preliminary but promising, especially given the dearth of effective domestic-violence interventions. In a pilot study, published in 2017, men who successfully completed an ACTV program were nearly 50 percent less likely to be rearrested for domestic violence as participants in Iowa’s old program. The Iowa Department of Corrections believed in ACTV enough to implement it in prisons statewide as part of prerelease programming. While the program is still relatively new, ACTV-based men’s groups have already been introduced in Tennessee, Vermont, and Minnesota.

As far as what, at bottom, causes domestic violence—why some men deploy violence to avoid unpleasant emotions instead of other forms of evasion—ACTV is agnostic. While participants are encouraged to seek out their own motives, ACTV classes are also designed to help them control their behavior in the moment.

In any case, while it might be satisfying to hear an abuser express regret for the harm he's caused, there’s no empirical evidence that taking responsibility does anything to make him less violent. Theoretically, a man could go through ACTV never admitting a single fault—could, in fact, believe that he is the victim in the relationship—and yet come through it a less dangerous man.

“I’ve had facilitators in trainings say, ‘Well, how can we even do this if he’s saying he’s a victim?’ And I’m like, ‘Who cares if he says he’s a victim?’ ” Zarling said. “He’s still going to learn these skills … Let him believe that.”

In the two weeks I sat in on the classes at Duluth, I often witnessed men venturing into uncomfortable emotional territory and glimpsing, possibly for the first time, some of the damage they’d wrought. There were tears, expressions of regret, pledges to improve. There seemed something undeniably valuable about giving men a forum to discuss subjects for which they had almost no language. Carol Thompson, who had been facilitating classes at DAIP for more than three decades, told me that many of the men in her classes had never talked about relationships before, in any context. At DAIP, they were forced to spend hours mulling over not just power and violence—the program’s purported focus—but what it means to be intimate with someone, to grapple with the implications of sharing another person’s life.

Still, even Ellen Pence found it difficult, at times, to square Duluth’s single-minded fixation on patriarchy with the infinitely messier reality of men’s emotional lives. While never disavowing its methods, in 1999, reflecting on DAIP’s origins, Pence seemed to cautiously backtrack on her original formulation of violence, in favor of a more expansive understanding of the phenomenon.

“Many of the men I interviewed did not seem to articulate a desire for power over their partner,” she wrote. “Although I relentlessly took every opportunity to point out to men in the groups that they were so motivated and merely in denial, the fact that few men ever articulated such a desire went unnoticed by me and many of my coworkers. Eventually, we realized that we were finding what we had already predetermined to find.”

By the final weeks of his court-mandated program, Andrew had begun looking forward to class. One day in 2017, a few weeks before the end, he stood up and spoke about his greatest fear. He was scared, he said, that he'd ruined his daughter’s life. He didn’t think she had ever seen him be physically violent, but she’d observed his anger and his drinking. He worried that she would grow apart from him. He imagined that, one day, she'd start dating someone like the man she had grown up with, and that boyfriend would hurt her. His announcement, which brought him to tears, was met simply, with a round of nods and a little eye contact—but that was enough.

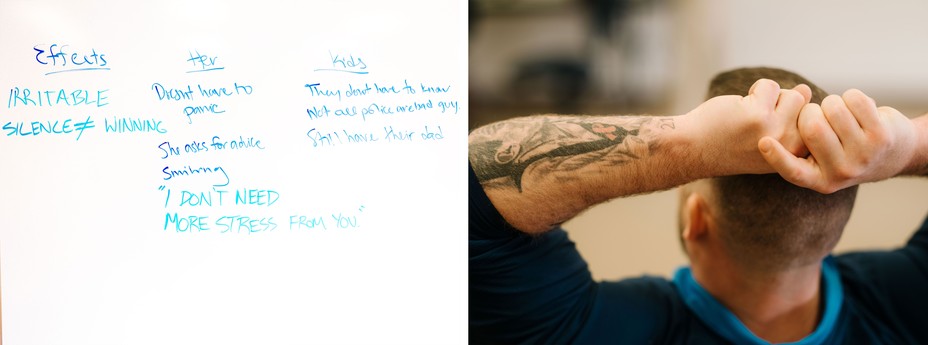

After leaving the program, Andrew finally felt like he had some control over his violence. The upside of taking responsibility for his mistakes, he found, was understanding that it was in his power to fix them. Gretchen, however, told me that only a few weeks after Andrew finished the program, his blowups returned. They were less frequent, only once every three months or so, and they didn’t culminate in physical violence. Instead, he’d send a threatening text or leave a nasty voicemail message.

While insisting that he’d refrained from any physical violence, Andrew admitted that he had, on occasion, returned to other bad habits. In the summer of 2018, after a bad breakup with someone he had been dating, he’d gotten drunk and received a DUI. In February 2019, Andrew checked himself back into DAIP, this time voluntarily. He’d heard all the lessons before, but the act of going—having to remember who he was and what he’d done—kept him on track, and he had no plans to stop anytime soon. “I’m just in a better place when I’m going to group,” he told me. “I’m still hoping that, one day, my abuse might be totally eradicated.”

From Gretchen’s perspective, as soon as her ex-husband was back in DAIP, he was, once again, respectful, patient, and sometimes even complimentary. He remained—as he’d always been, even during the worst years—a wonderful father. After almost a year attending classes, Andrew became engaged to a woman named Theresa. He is currently seeking to become her 3-year-old daughter’s adoptive father.

That said, there were limits to Andrew’s rehabilitation. Gretchen said he had never apologized to her for his violence, and that when Andrew reached out to her asking if she’d be willing to be interviewed for this article—about “my abuse,” he wrote—it was the first time she’d seen him use those words. (Andrew said he has apologized multiple times.)

“I don’t think he’s fundamentally changed,” Gretchen said. “But I do think he’s getting tools to learn how to cope.” Sometimes Andrew used those tools, and then sometimes—even after all those hours of class—he did not.

In October, Gretchen posted a message on Facebook in honor of Domestic Violence Awareness Month. An hour later, Andrew left a comment below it: “You love so much to be seen as the victim.”

This article is part of our project “The Presence of Justice,” which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.